It was one of those bedtime moments when there’s a choice as a parent. Do I say ‘not now’ or do I engage in the topic? It was a chance to talk to my children about war. Understandably, not one I relished, but then I’d rather they hear it from me than somewhere else.

To give some context, my made-up bedtime story had included a fundraiser for refugees. We ended up talking about a friend from Iraq who is seeking asylum here and I explained that he’d come to the UK to escape a war in his country. So really, I had invited the discussion.

What’s war like?

What’s war like? My 8 year old asked me. It’s horrible, I said. I mean I want to know what it’s like, he persisted. Is it like two teams where people shoot at each other? I think he had laser quest in his head as he said this. What happens mum?

I could see that he wasn’t going to let it go. I was in a dilemma. I didn’t want to fob them off. Children know when you’re doing that. And I didn’t want to get too graphic either. My four year old was also listening attentively and waiting for my response. How could I talk to my children about war?

How to talk to my children about war?

I gathered myself and tried to explain some of the edited reality of war. I told them about drones and what a bomb is and how innocent people get injured or killed. I explained that our friend had lost his family. I talked about feelings of grief and sadness.

I explained how lucky we are not to have experience of war. I reassured them that there is no war in our country. I sang them to sleep. I was worried that they would have nightmares or wake up in the night afraid.

An interesting response

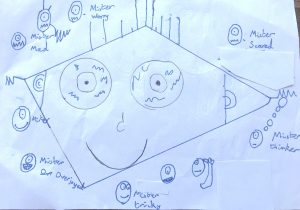

Thankfully, they both slept very well and the next morning my son came to me to excitedly show me a picture he’d drawn. It was a series of hand drawn emoji pictures with feeling descriptors next to them.

What’s that? I asked. It’s my feelings team. Is that something you’ve been doing at school? No I just made it up, I’m going to make a comic.

In the weeks since then we’ve had the summer holidays and the chance to talk about our beliefs about violence and peace. I studied these things when I did my Masters. As a result, I believe that most violence comes about when basic human needs are not met, needs for food or shelter, or for the chance to contribute through meaningful work or respect.

The link to climate change

As I write this, the international day of peace is imminent and the focus is the climate crisis. We also prepare to take our children out of school for a day for a global climate strike. We’ve tried our best to explain the implications of climate change. We’ve talked through the value of protesting nonviolently. My son is nonplussed, he hates any conflict and my daughter is delighted as she loves to try anything new and is not averse to confrontation!

However, if we are talking about basic human needs this issue feels too important to ignore. This is our future, this is their future. As I’ve learned time and again in my work with people in conflict, if we ignore an issue it doesn’t go away.

I, for one, want to learn how to talk to my children about war. And climate change. And all the other topics that are sometimes easier for me to avoid.